Welcome to November.

During the harvest season, we are all reminded of our agrarian roots, though most of us no longer work outside. Thousands of years ago, our first steps towards taming nature offered humanity a new sort of freedom, though it gave rise to a new set of problems.

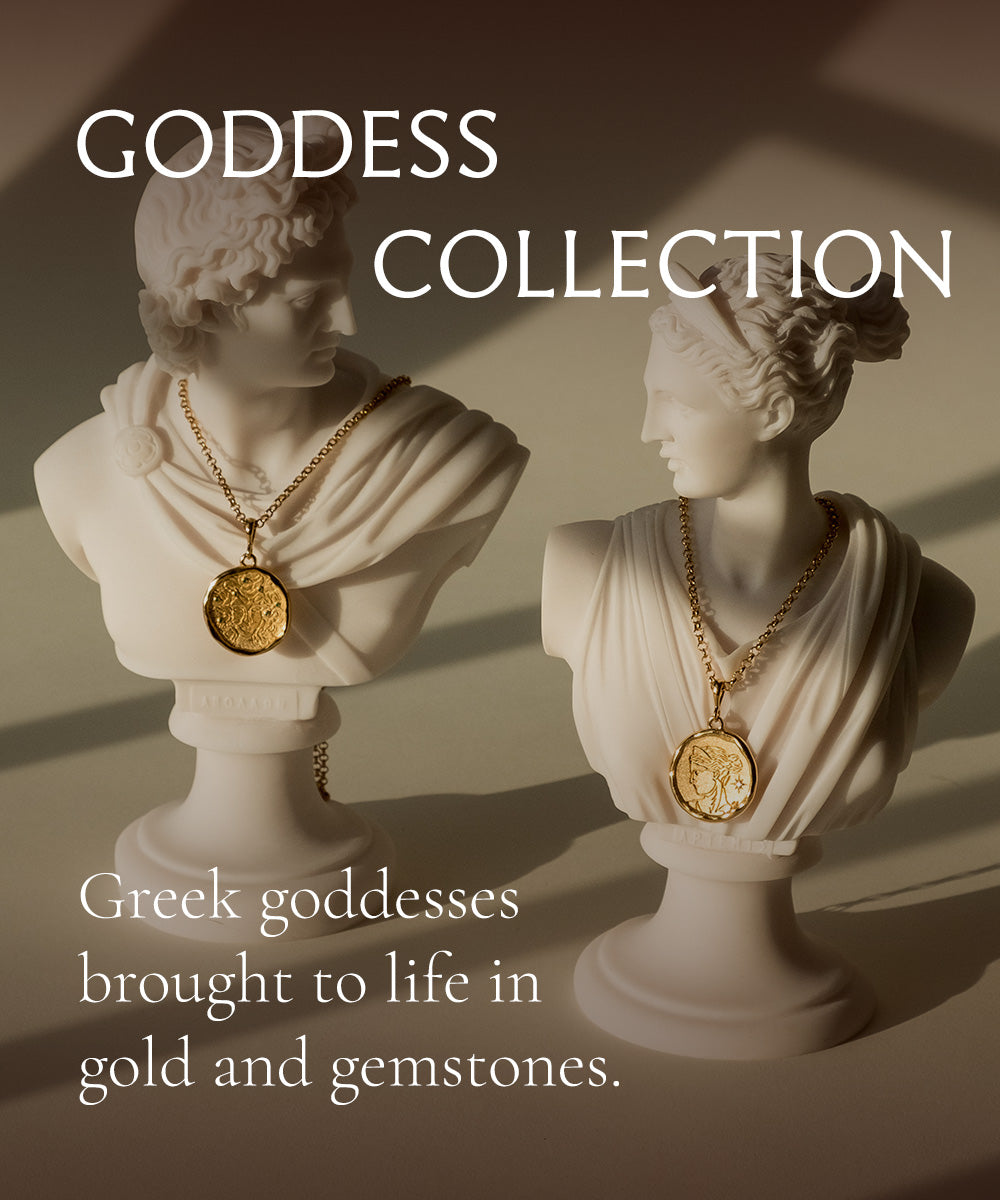

The success of a harvest is never certain. Somewhere between food storage and a starving winter, human life hangs in the balance. It was only natural that, when faced with such uncontrollable and potentially catastrophic things, year by year people sought the help of the gods. In ancient Greece and as far back as three thousand years ago, the harvest festival Thesmophoria was held every year to sweeten the goddesses of agriculture and seasons, and to nudge that precarious balance in humanity’s favor.

Thesmophoria was celebrated in late autumn to honor Persephone and Demeter, that they might bless the fertility of the land and ensure the bounty of the yearly harvest. Unlike most festivals, or most of anything really, Thesmophoria was celebrated only by women.

In order to tip the scales and usher in another prosperous harvest, women would gather every year to supplicate for Demeter’s blessing. Though it was one of the largest Greek festivals, we have little evidence of what they did, as women were neither taught to write nor permitted to tell men about what they did. The festival changed over time and from place to place, so it is impossible to say exactly how it went. Here is the knowledge we do have.

The three day long celebration included ritual purity, cakes baked in the shape of snakes (and other snake-like appendages), fasting, hymns, and sacrifice. On the first day, the ascent, married women would make a procession to a nearby city or up on a hill, depending on where they lived. This day and for the next two days, the women concerned themselves with chastity and ritual purification.

The second day was one of mourning and fasting, an echo of Demeter’s mourning during Persephone’s disappearance. The third day was bright and joyful, full of singing, sesame honey cakes, and the prospect of new life. At some point, pigs were ritually sacrificed, buried, and exhumed by these women to please the goddesses and offer atonement for any wrongdoing.

Because men were not permitted to join the festival, these Greek women had, if only for a few days, a sort of freedom to which they were usually not privy. Today, we see the problem in only allowing women individual agency within a fertility festival—thus signifying that fertility matters are the only thing women can be trusted to handle—in that way, it is dehumanizing.

Ancient Greece is not particularly known as a paragon of women’s rights.

There actually is some modicum of sense to it, if you view it metaphorically. Childbirth is particular to women, and painfully similar to the harvest: it could bring about new life and sustain humanity, but it is uncertain, and if the smallest thing goes wrong, it can be deadly. To Greek men who didn’t want to concern themselves with such womanly issues, and who were more than a little afraid of the wrath of Persephone and Demeter, it was easier to just let the women handle it—they always have.