“Sweet, incomparable Joséphine, what a strange effect you have on my heart. Are you angry? Do I see you sad? Are you worried? My soul breaks with grief, and there is no rest for your lover; but how much the more when I yield to this passion that rules me and drink a burning flame from your lips and your heart? Oh! This night has shown me that your portrait is not you!”

- Napoléon, in a letter to Joséphine, December, 1795

Napoléon commanded numberless men, whole armies and military strategies, and ruled the entirety of France. But Napoléon himself was ruled by Joséphine.

She was married while still very young. Being the daughter of impoverished aristocrats, she was married off for money. The marriage was cold at best, but Joséphine had a daughter and a son by her first husband.

The revolution changed everything. Joséphine, who still went by Rose at the time, lost her husband to the guillotine and was herself imprisoned. By sheer luck, was released after the July 27 coup d’etat, and she was determined to rely on her guiles and wit to ensure the future of herself and her children.

Napoléon was obsessed from the moment he met her. Joséphine was striking, with her large eyes framed thickly with long lashes, her low, sultry voice, and her unending charm and grace that would weaken the knees of any red blooded man.

The couple exchanged love letters during the time Napoléon led the French army into battle. His letters were fiery, full of yearning and lust, but hers were infrequent and coy, if even reserved, leaving the infatuated army officer to languish.

Joséphine agreed to marry Napoléon, and as he rose to power, she used her contacts to further his interests. Ten years into their marriage, he became emperor, and she became empress.

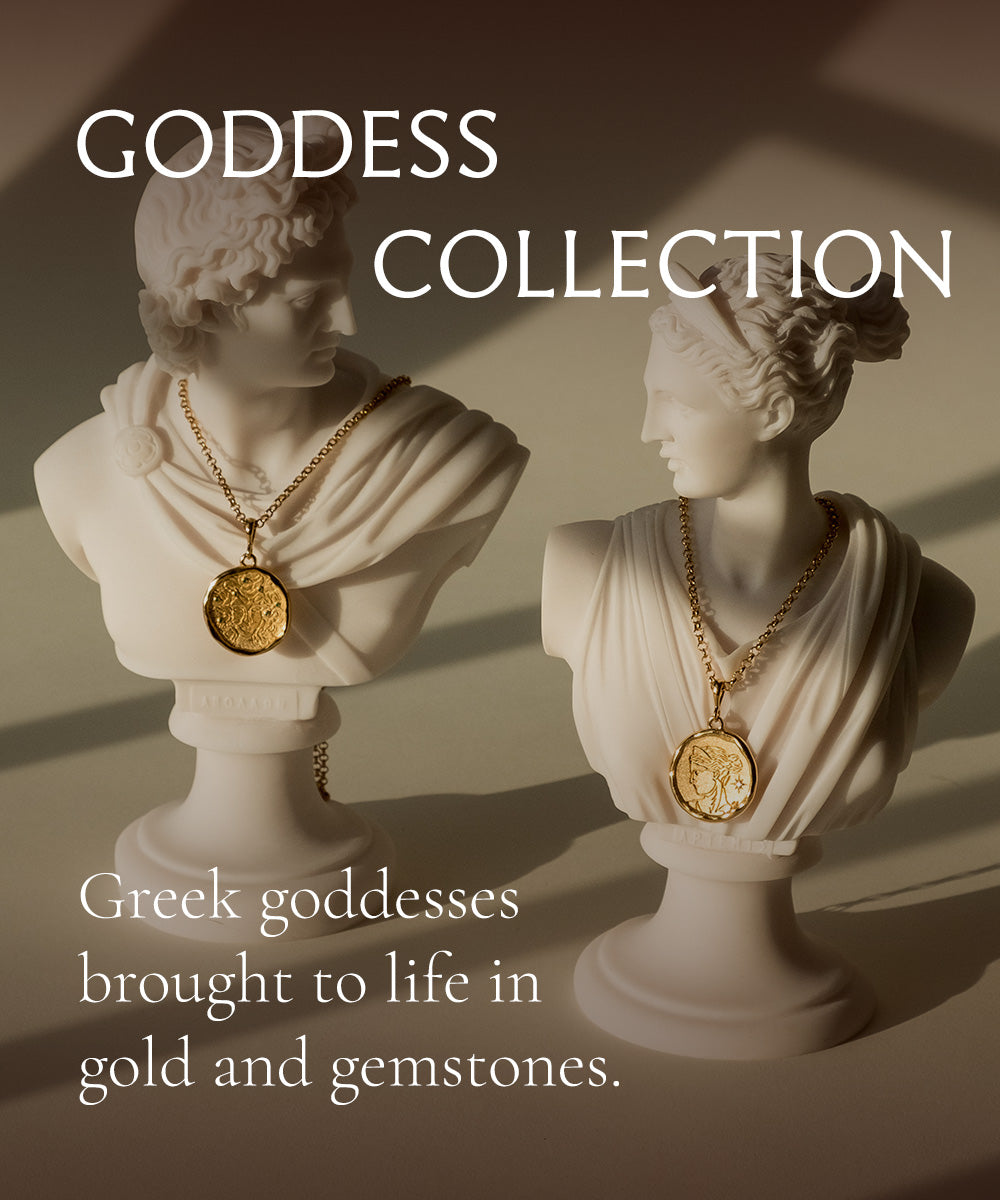

Empress Joséphine was a bit of a classicist, interested in ancient artifacts, particularly those found in the excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum. She had a penchant for ancient Roman cameos, hard stone carvings depicting goddesses and myths. Her neoclassical style often called up old Greek and Roman symbols, like laurels and oak leaves. On the day of her first ceremony as sovereign, she wore a tiara fashioned like sheaves of wheat, frozen in silver, but delicate enough to look as if they swayed with her dark hair in the light morning breeze that swept through the Parisian church.

Acrostic jewelry — that which spells out a message with gemstones — began with Napoléon, who gifted his Empress Joséphine two acrostic bracelets that spelled out the names of her children, Hortense and Eugène. This was a gift of love, of devotion, and shows a deep understanding of the woman’s heart.

She passed on before him, they say of a broken heart, but years later her name was Napoléon's last word on his deathbed: “France, l'armée, tête d'armée, Joséphine.” France, the army, the head of the army, Joséphine.