“You only have to look at the Medusa straight on to see her. And she's not deadly. She's beautiful and she's laughing.” -Hélène Cixous, Laugh of the Medusa

When I was a teenager, I suddenly became acutely aware of the paradox of female desire. I was attending a new high school, and my only friend was a childhood acquaintance, a boy who lived in my neighborhood. I was grateful to at least have someone to sit with at lunch, at least until the gossip made its way to me. Being called a slut at the lunch table was equal parts horrifying and confusing, and though I acted like I didn’t care, I sat alone until I made female friends.

A decade later, I can wave this away as the casual cruelty of teenagers. But there is something deeper and older within it, something structural and deliberate. I had changed a normal, healthy behavior for fear of being treated differently or badly. At the time I sensed that what I was experiencing was specific to women, but I did not stop to wonder why I was changing myself for people whose names I did not know, or what gave them the right to judge me or my perceived sexuality in the first place.

It’s no secret that sexuality and shame are tools used to control women. It really does not matter what behavior you exhibit, because you are damned if you do, damned if you don’t. Dare to assert yourself against this backwards logic and you’re just vile, you witch, nasty woman.

“…she has always occupied the place reserved for the guilty (guilty of everything, guilty at every turn: for having desires, for not having any; for being frigid, for being "too hot"; for not being both at once; for being too motherly and not enough; for having children and for not having any; for nursing and for not nursing)…” listed so, you begin to see that it was never about the choices she made. It is about being a woman in the first place.

The impossible standards we hold women to are so deeply ingrained in the foundation and structure of society, history, and culture that it becomes normal and acceptable for teenage girls to call each other sluts for things as innocuous as eating lunch with a boy. It maintains the patriarchal status quo, so much so that when assault takes place, women are blamed for being victims as quickly as they are blamed for defending themselves.

Such as Medusa, a victim of sexual assault who was turned into a Gorgon in the name of justice, which is a rather drastic solution. To be literally untouchable seems miserable, and to me, it sounds like she was victimized all over again. Those who have experienced how the justice system handles sexual assault today will note how familiar this sounds. It makes one wonder if this is a feature, not a bug.

At the very least, in her serpentine form, Medusa was finally able to protect herself. But then she was called a monster, an evil hag who turned innocent men to stone, when all they did was try to cut off her head. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t, since the beginning of time.

Of course there is a crack in the facade. It simply isn’t real. It is a construct, built on nothing of substance. The shadows on the wall tell you slut = bad, because when a woman takes her sexuality into her own hands, says yes or no based on her feelings and hers alone, everything the patriarchy has built up to keep her in her place falls apart.

Wave away the smoke and it will dissipate at once. When women start asking questions and sharing stories, the patriarchy is left scrambling, desperate to push her back into the box they wish her to live in. It is no wonder they are terrified.

This fear of female agency is the basis upon which Medusa’s legacy was formed. “They need to be afraid of us. Look at the trembling Perseuses moving backward toward us, clad in apotropes [wards against evil].”

This is why Medusa is called a monster. Powerful women must be demonized, else more women will feel empowered, and they will escape the patriarchal structures meant to hold them in place. It is a smokescreen designed to hide women from themselves, because a woman who sees no reason to feel shame about her sexuality or womanhood cannot be controlled by either. In her desire lies her freedom, her inherent value, and agency that was always hers—she only needs to acknowledge it.

While these constructs are not based in reality, the harm that comes from them is very real, and incredibly damaging. Medusa’s story is a tragic one. Perseus beheaded the Gorgon and used her for his own affairs. But here, in tragedy, I see the true power of Medusa: by being disembodied, she became godlike with the power to exact vengeance, a raging symbol of female autonomy. But she is not meant for Perseus. She is meant for you.

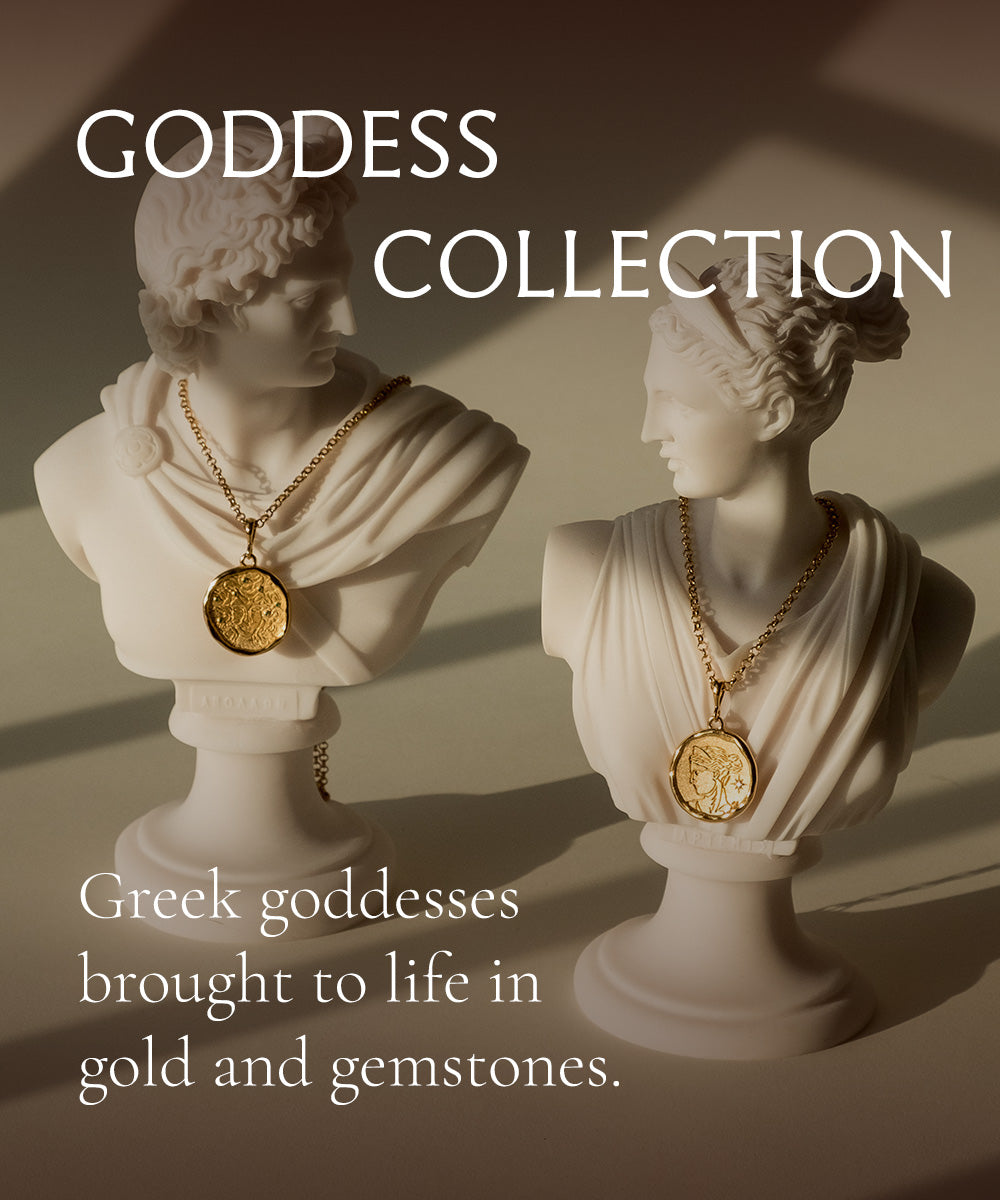

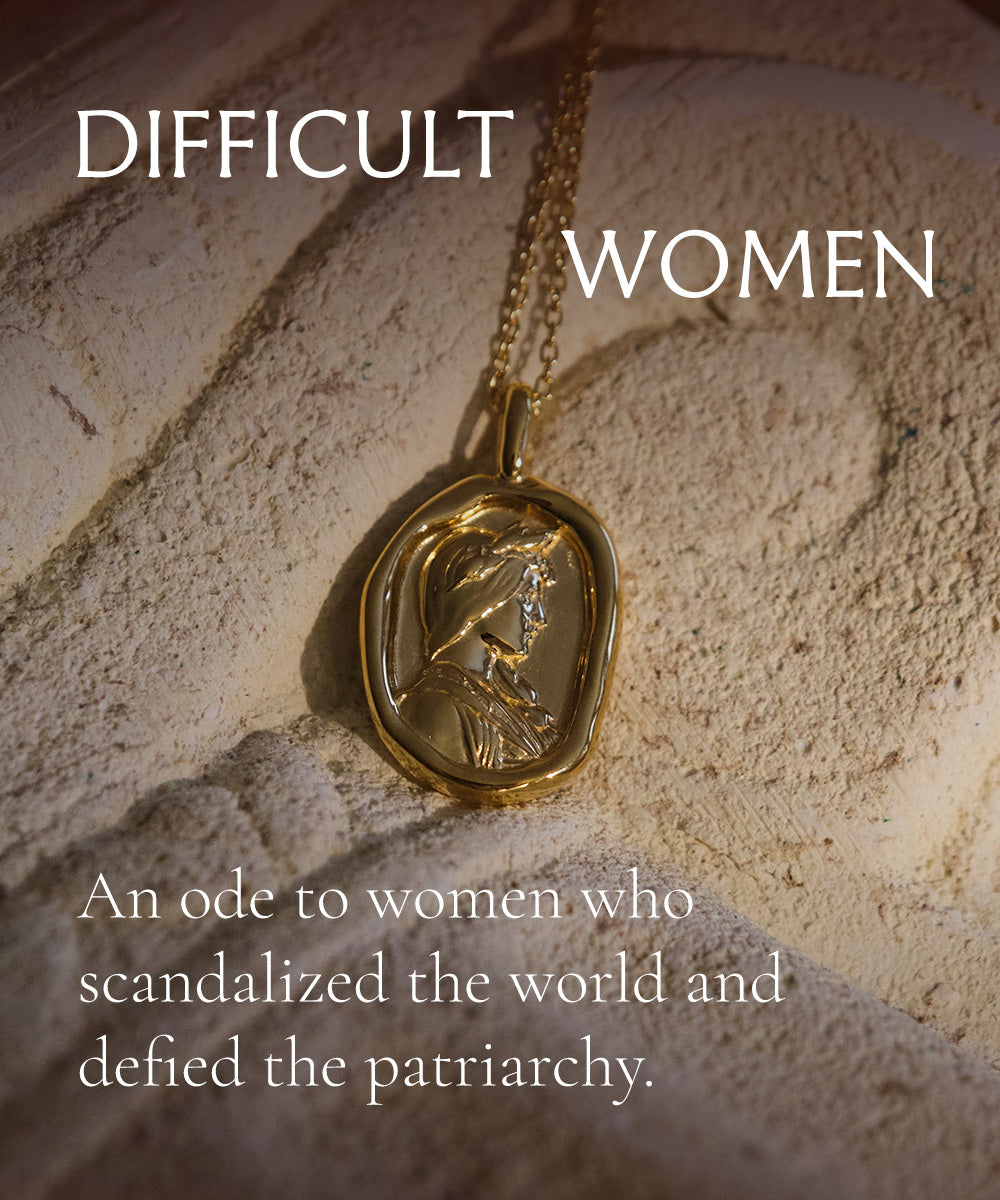

Athena wears Medusa on her shield, the aegis. She goes into battle armed with all of the fury of guardian and protectress Medusa. And so will you, on your shield, around your neck, a piercing third eye in the center of your forehead.

And so all that is left is to look at the Medusa head on: to support and contribute to the narrative, to believe women, to honor your own body in whatever way you see fit. To look at Medusa in the mirror, and find she is not frightening, nor monstrous, and you have not turned to stone. She is exactly what you knew she would be. She is free, she is unashamed, she is beautiful, and at last, she is laughing.