Gold is a shapeshifter. It doesn’t degrade or corrode; it merely changes form. A fleck of gold can hold the story of the world.

One fleck begins its life 200 million years ago in the heart of a dying star, then shoots through the nothingness of space and collides, violently and improbably, with our fair planet. It is ferried first by molten rock, and then by hurried rivers, only to settle in the crack of a creek bed, waiting to be found and molded and admired.

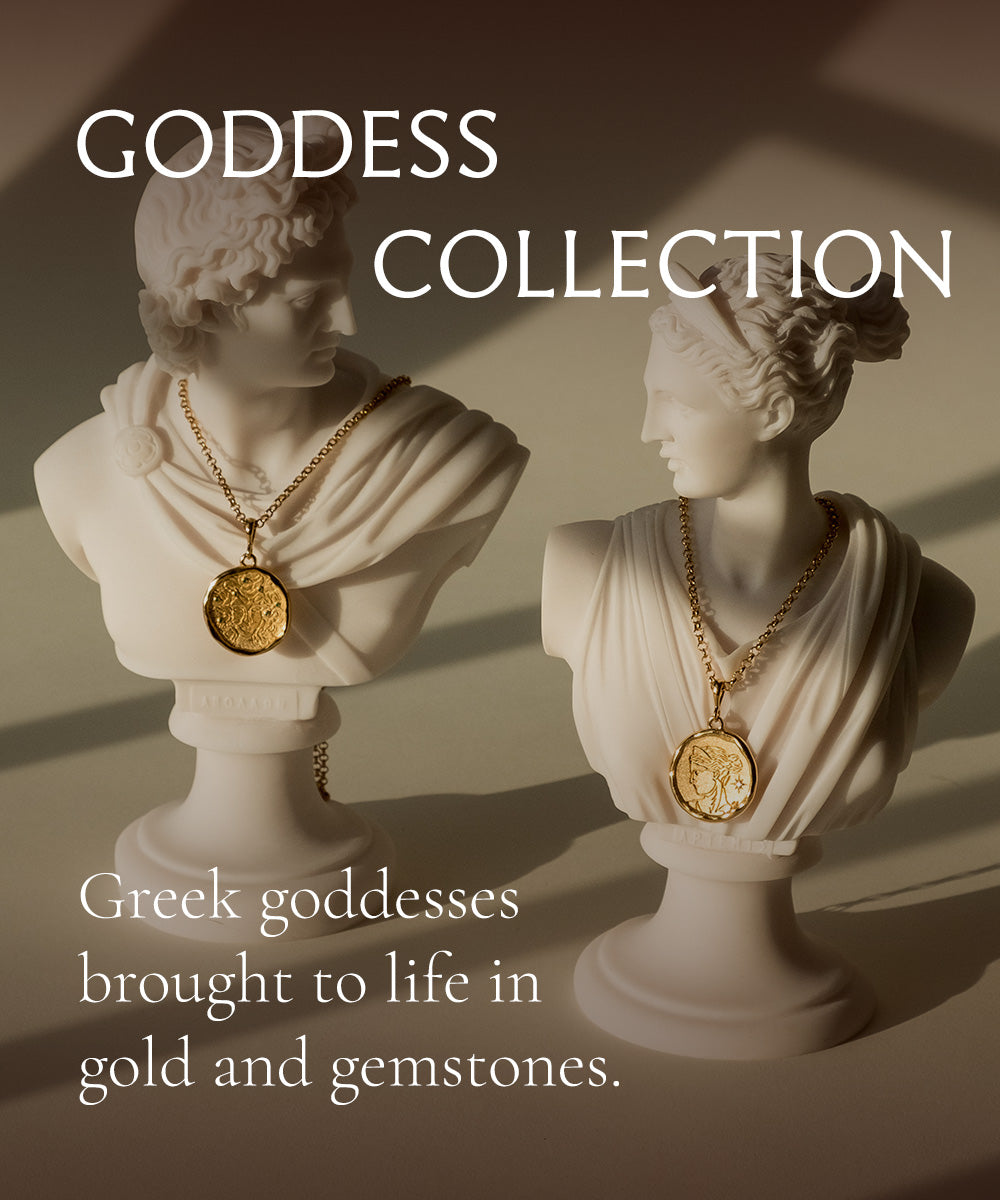

Our fleck, scooped up washed off, is layered delicately on a statue in the Parthenon where it gleams in Athena’s honor until desperate Athenians pry it off as war with Sparta bleeds their treasury dry. It finds its way to the Romans and is melted, hammered and stamped for coin. It passes hands again, again, again: for livestock; a villa on the Palatine; a soldier’s service.

It reaches Constantinople in the purse of a trader. It is slipped into a jeweled gold cross by the hands of Byzantine goldsmith and carried across the stormy seas to an Anglo Saxon monastery, where it watches generations of monks copying sacred texts. It bides its time. Henry VIII breaks with the church; the cross is snatched and sold to the highest bidder, whose descendants will eventually tire of its garish nature, so at odds with the new church. They re-work it into a bracelet set with pearls and rubies. The bracelet adorns wrist after wrist of English ladies; it tinkles merrily against delicate champagne glasses.

War comes and champagne glasses are put away and fortunes are ruined. Our fleck crosses the seas again to New York, accompanying hopes for a better life that will be dashed in November 1928. The bracelet is pawned in a little shop downtown where its rubies and pearls are pried away and its gold is melted down. The little fleck is left in a storeroom with its companions, waiting to be shaped into a ring that grows warm on the skin, as only gold can.